Melbourne is projected to be a big city, so it should start thinking like a big city.

– Dr George Quezada, Innovation Scientist

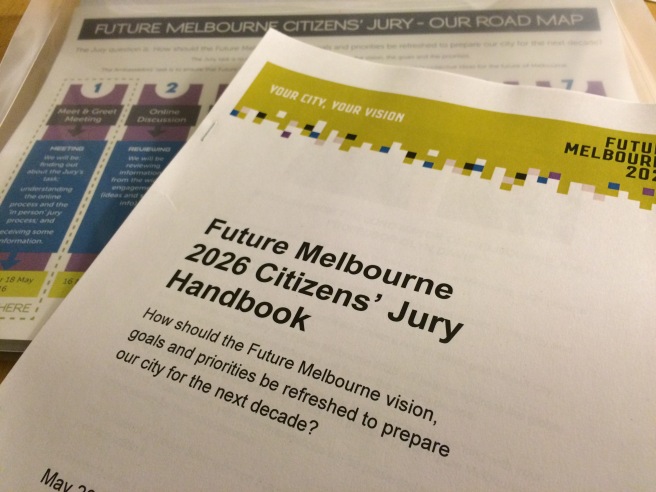

I’ve just completed day 1 (of 3) for the Future Melbourne 2026 Citizens’ Jury process. We on the jury are a bunch of 60-odd randomly selected residents and business owners of the City of Melbourne who are helping to deliver the third and final phase of the council’s Future Melbourne plan to 2026.

This involves delving in detail into the report Future Melbourne 2026: Bringing your ideas together, and deciding on the final goals and principles to put forward to the six Future Melbourne Ambassadors to take to Council in August 2016.

I’m passionate about the future of this city, and wanted to be a part of this jury process to speak up from a library-loving, learning-focussed perspective. I’m interested in getting across the idea of needing good governance and planning in place for as-yet-unknown applications of new technologies throughout the city. I want to learn more about how to contribute to making this a sustainable city. Working in the information management world, I want to speak for sustainability of knowledge and information – particularly if there are to be improvements and increases in the partnerships between research organisations, government, and business, in order to drive innovative new projects.

The quote that opens this post is from guest speaker on day 1, George Quezada, an Innovation Scientist at Data61.

George noted that as people are able to access more information, and more data, about various processes that govern our everyday lives, and as they begin to analyse that data, those people will increasingly be able to challenge those in authority.

Transparency of information enables empowerment through increased knowledge.

George talked about the idea of establishing ‘future precincts’ in cities, and pointed to one example, Samford Commons, which he is putting his energy into delivering after receiving substantial funding from The Moreton Bay Regional Council. The Samford Commons annual report from October 2015 expands the concept of their model in more detail.

Future precincts have captured my imagination: they are spaces that can’t be prescribed in advance; they must remain as free, constantly changeable spaces that will sow the seeds for new strategies to emerge to manage cities better. They must have the freedom to experiment with bold visionary ideas in a space that is conducive for careful failure. Samford Commons states that it will:

Host conferences, conduct accredited environmental management programs, sell natural produce, hold demonstration field days, conduct school programs, support sustainable industry co-working, manage a connection to the broader community and provide daily programs and innovative activities for businesses, schools, tourists, community members and on-line clients.

This is one way to tackle future challenges – for governments, councils, and citizens to be guided by the learnings and failings of these future precincts. As George put it, future precincts are demonstrations of a resilience strategy – providing outcomes from new modes of operating, these precincts may provide a means for a community to meet unexpected challenges. And it can be done much more effectively by utilising the strengths of all sectors – research, business, government, in increasingly connected ways.

Taking these ideas for the Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums, and Records (GLAMR) sector, wouldn’t it be great to have an information/cultural heritage voice in these future precinct spaces, for testing out new theories, ways of doing, ways of interacting with other sectors, and the community? Having true convergence and experimentation between sectors to learn from each other’s wins and fails?

The iGLAM research centre comes to my mind, the Laboratory for Innovation in Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums, as a prototype that could be put forward to begin to play in this wider space in partnership with government, business, and communities.

I was also reminded of the Innovation Study from 2014, Challenges and opportunities for Australia’s galleries, libraries, archives and museums, which clearly identified four strategic initiatives:

- Making the public part of what we do

- Becoming central to community wellbeing

- Beyond digitisation – creative reuse

- Developing funding for strategic initiatives

This report is an interesting read, particularly as various milestones for 2016 are detailed in it. And I’m also thinking a lot about how my voice on this jury can help further the agenda to ‘make the public part of what we do’ and especially how we can become even more ‘central to community wellbeing’.

Other notable things that stood out for me about my citizen jury experience:

Ben Rimmer, Chief Executive Officer of the City of Melbourne, spoke to us about the challenges around balancing the different needs of residents, business, students, visitors –and drilled into this further by explaining how difficult it can be to balance financing and resourcing for the basic everyday essentials that run a city, versus the ‘nice-to-do’ elements that enhance a city. He mentioned that the ‘nice-to-do’ extras that the City of Melbourne invests in are exactly the things that make Melbourne a great city. Another of Ben’s observations was that tech developments are coming ‘thick and fast’ to change the way our city operates (robots in the drains, location services technology placed in rubbish bins, autonomous cars not too far away now) – and his ‘professional guess’ that the next ten years will see technology change have the biggest implications for the city.

Maria Katsonis, Director, Equality, in the Department of Premier and Cabinet (Victoria), is one of the Future Melbourne Ambassadors. She spoke about the importance of workplaces allowing and enforcing an allowance of bringing your true, authentic self to work everyday. As she said to us, ‘two years ago, I wouldn’t have been wearing rainbow shoelaces to work’, pointing to her colourful laces. Maria spoke of Richard Florida’s The rise of the creative class, and how it raises the question, can you attract a certain type of person to a city?

Maria’s parting consideration for us was most interesting, as it echoed what I’d heard in a lot of the discussions during the day. When going through the report, and deciding and debating what’s in and what’s out, we should always be thinking: who’s excluded from this plan? Does it truly reflect the needs of our diverse community? Does everyone have a voice, a place in it?

Kate Auty, another of the Ambassadors, in response to my question wondering who the visionary leaders are in the sustainability sector that she looks to, that we can seek out – the change agents – she answered, ‘It’s all of you – you’re all leaders. Start where you are, and organise’. Her example of this idea in action came from her experience, being involved in a campaign seeking (successfully) to change some entrenched mindsets (a group of farmers) toward climate change.

This jury day was extremely intense. It was a day of testing assumptions, questioning, and learning.

For anyone considering a chance to participate in this kind of process in future, here are some select thoughts gathered from myself and others about our day, paraphrased:

Participatory democracy feels like proper governance, the way things should be.

There is a feeling of more investment already in the outcomes, over just one day – much more so than going to the ballot box and picking from a bunch of fixed policies.

Diversity is all about inclusivity.

It seems to me that participatory democracy is something that the community is hungering for: this two-way communication activity that has been offered to us has been accepted, and trust that the council will implement our work has been established.

This process is invigorating. At the end of day 1, I’m completely engaged with and addicted to citizen-led and citizen-influenced democracy.

The challenge for me on the next two jury days is to look beyond my priorities and areas of interest to see how they fit in with the bigger picture goals of this process – to refresh the goals of a city for the people, one that is creative, prosperous, full of knowledge, sustainable, and connected, and that reflects a bold and brave vision of what Melbourne could be in 2026.